“Some girls can skate, but I personally believe that skateboarding is not for girls at all. Not one bit.” - Nyjah Huston

On May 30, 14-year-old skateboarder Arisa Trew became the first female to land a 900, a feat accomplished less than one month before the 25th anniversary of Tony Hawk's first groundbreaking 900 at the X-Games.

I watched the video of Trew nailing what is considered one of skateboarding’s most demanding tricks and promptly burst into tears. Then I watched it again and again and again, delighted by her reaction and the jubilant reactions of her friends.

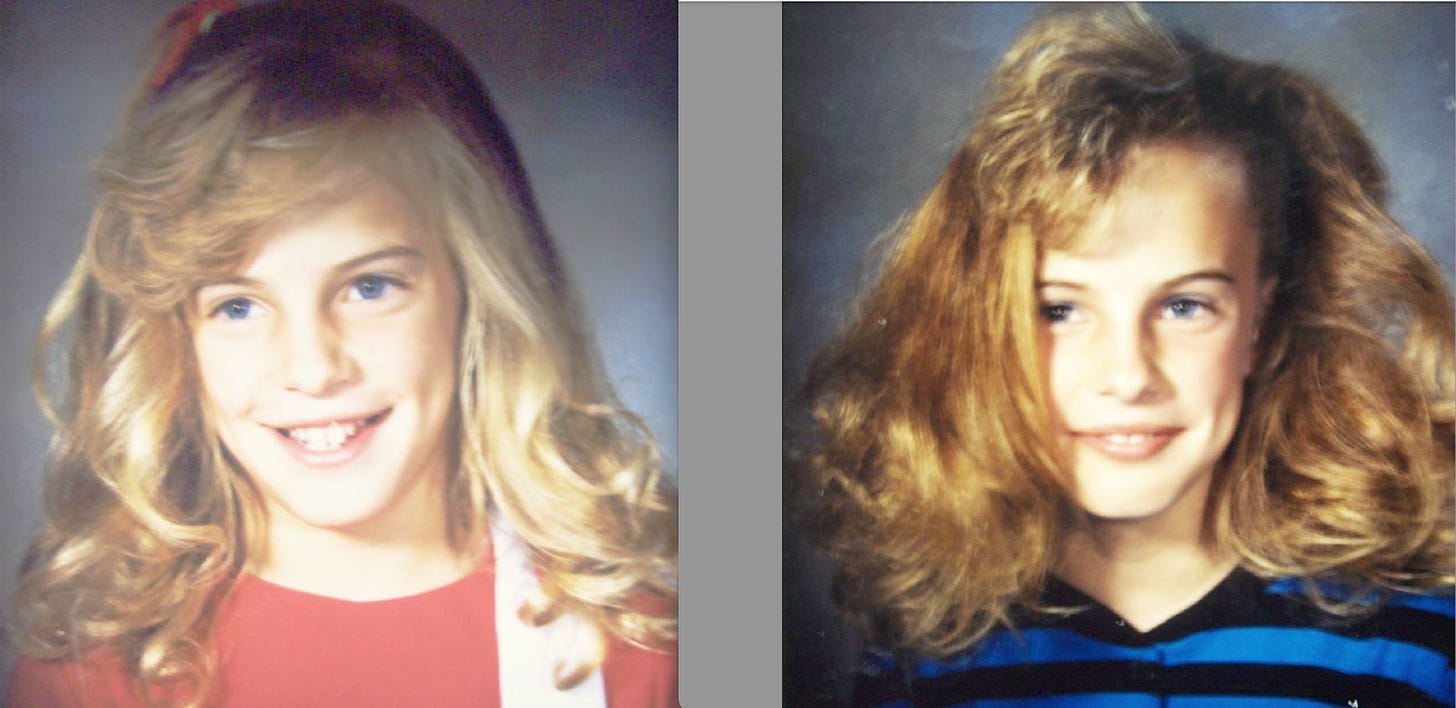

Initially, my tearful response surprised me. But the more I thought about it, a flood of memories came rushing back and my reaction made sense.

You’ d hear them coming before you’d see them.

Thump-thump. Thump-thump.

The heartbeat of skateboard wheels on sidewalk.

Thumpthump - glide - thumpthump - glide - thumpthump - glide.

A very specific sound that still thrills me all these years later. Whenever I hear it, I instantly search for the skateboarder. In the late 80s, the double thumps as the front then back wheels smoothly navigated sidewalk cracks felt like the beat of my 10-year-old heart filled with the fiery passion to make that noise myself instead of hearing it from the sidelines as neighborhood skater boys rolled up to hang out with my three-years-older brother, Brandon.

There were no skateparks in 1987 Utah. Wouldn’t be for many years. And there were no empty swimming pools. No full ones, either, for that matter. Ain’t nobody within a several mile radius of my neighborhood with enough dough for the kind of pool that couldn’t be driven from Kmart at 20 mph while everyone with a window seat cranked an arm out to firmly hold the upside down plastic pool shell to the car roof, god forbid wind catch the rim and flip it up during the ten minute drive home.

The skateboard clatter of boys improving ollies, kickturns and kickflips floated through my bedroom window more days than not. The telltale scrape, bated breath of silence indicating airborne-ness, before a grinding landing followed by a raucous cheer as someone mastered a new trick was always exciting.

Always the watcher, never the skater, I’d put down Anne of Green Gables, The Babysitters Club or Sweet Valley High to rush to the window and peek out at the congratulatory high fives being shared.

I desperately wanted to skateboard. But there were no girl skaters, at least none that were on my radar. Not in the few copies of Thrasher or Transworld I managed to get my hands on after my brother had thumbed them to tatters and certainly no girl skaters in my little chunk of Utah next to BYU, Mormon capital of the universe.

Skateboarding was strictly a guy thing and my role - if I could be said to have one at all - was to stand around cheering them on as they jumped curbs, ramps and traded tales of ditching overzealous small-town cops who tried to prevent them from skating pretty much everywhere.

After watching my brother score a new Powell Peralta deck he meticulously tricked out with wheels, bearings and stylish grip tape, I asked for a skateboard for Christmas. Maybe Santa Claus would hook a sister up?

Alas, while Brandon got the real deal and all the badass accoutrements, I was gifted a cheap plastic deck with plastic wheels that barely turned that appeared to have been procured from the toy aisle of Kmart.

Still, I practiced ollies and 360s when no one was watching and secretly wore my brother’s Vision Street Wear T-shirts to school even though a beating was most definitely in the offing if caught.

So I fucked around on my plastic skateboard in our garage and driveway when no one was around. It was not a thing I was comfortable doing in front of my brothers or the dozen skaters he hung around whose biggest burns involved calling each other “little girls” and “pussies” when someone was afraid to try to drop-in or attempt a trick on the little street ramp he built in front of our house.

“Having a girlfriend that skates is as bad as having a girlfriend that strips.” - Clyde Singleton

In 7th grade, my boyfriend, a skater, gifted me with a photo of Tony Hawk he managed to get signed when Hawk came through Utah for a skating competition. A signed Tony Hawk photo! Clearly we were very serious about each other. And still, even within the confines of this relationship, he was the skater and I was the cheerleader, a Tony Hawk fangirl.

First kiss. 8th grade. Dave Tate, owner of blonde floppy bangs that hung over beautiful blue-green eyes in a sexy swoop that made my bony 13-year-old knees weak with longing. I knew Dave was coming down the street long before he arrived by the sound his skateboard made as it glided over the sidewalk.

Dave’s skating was smooth, his soft wheels veritably caressed the pavement. Other boards rattled over the concrete sounding like broken air conditioners as loose, dirty bearings and bolts fought each other, but not Dave’s. His skating was as smooth as his personality.

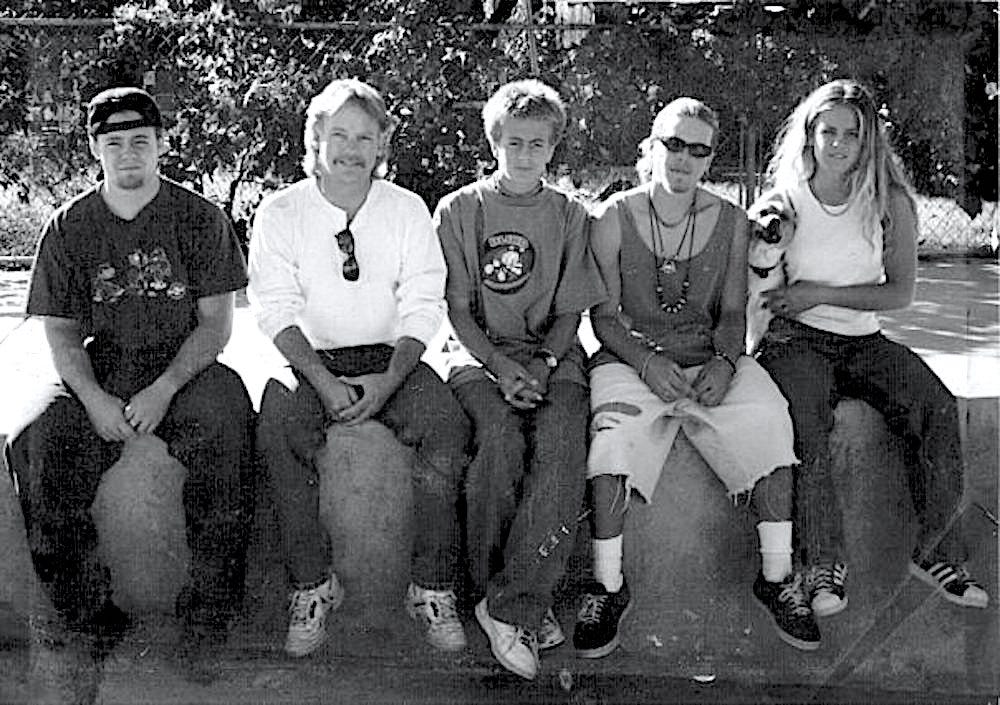

In 1988, my older brother and a friend stole lumber and tools from a construction site and built the first half-pipe Orem, Utah had ever seen in our backyard. A popular local skater spray painted the Bones Brigade skeleton tearing out of the ramp and our backyard became a skater’s mecca and I was known as “Butler’s little sister.” I’m sure the Mormon neighbors loved it.

I would ingratiate myself with the dozens of skaters who came from all over to see if they could drop in on the ramp by handing out snacks and pops, as we called them, often buying them with my own money from the convenience store down the street. Ever the perfect hostess performing her divinely inspired female role of serving the men who get to do the fun, scary, cool things. Gender segregation: boys will be boys while the girls play supporting roles. Fuckin’ story of my childhood.

Although it’s not so much like this anymore, late-eighties skate culture was synonymous with counterculture, rebellion, breaking the rules, and a rejection of the mainstream. An exciting punk rock mentality that those seeking to live outside the conformist box unconsciously gravitated to, including me.

It’s why I have always liked being around skaters. They epitomize anti-establishment surfer chill, forever scoffing at over-aggressive officers of the law in ways I find deeply gratifying. I will always root for the outsider, the anti-conventionalists for whom conforming is a kind of death. While money trauma propelled me into a life of walking a conventional job-having tightrope, the defiant, rule breakers are my people.

Correspondingly, I grew up disliking and distrusting the all-white, Mormon police in our city who raided our home several times for drugs, arresting one brother or the other for various crimes, leaving behind torn open couches and mattresses, ransacked closets and drawers for me to clean up.

‘Skateboarding is not a crime’ was a slogan developed in the late-eighties by Powell Peralta in response to the constant harassment of skaters and the mainstream refusal to recognize it as a legit sport.

The skaters in my neighborhood were regularly telling exciting tales of evading cops and security guards and sharing where you shouldn’t skate if you wanted to avoid being hassled or where you should skate if you wanted to piss off certain police officers and business owners. I delighted in hearing their skateboarding adventures and triumphs over the law but they were always just stories. I was never there.

*****

My son went through a skateboarding phase I like to think I gently inspired and I suppose I tried to crowbar my way into the fun and live vicariously through him.

During the pandemic we logged many hours at a handful of skateparks and built a half-pipe in our yard.

Ultimately, maybe I was more into skateboarding than Henry, who appears to have moved on although he has many teenage years ahead of him so I haven’t totally given up the ghost. But, as we learned after several years of endless and sometimes terrifying Little League games, you can’t force a kid to persist at something that doesn’t spark joy within them like it does for you. All you can do is introduce what you love, offer gentle guidance and get the fuck out of the way so it can go where it’s going to go.

In the fantastic documentary, Building Skateboarding’s Future, about the inception and evolution of skateboarding, (released by 900 Films, a company Tony Hawk founded) Hawk talks about skateboarding in a way I immediately recognized at a gut level.

“Kids that go to the skate park for the first time, I think they see the daredevil antics and the excitement and the vibe. Even if they’re not there to skate, they’re drawn to it. And when people find it, they’re stuck in it.”

Just as in the early days, when empty pools were transformed into skating havens or resourceful delinquents like my brother built ramps, skaters embody a do-it-yourself dedication, turning abandoned or unused spaces into obstacles to be conquered. It’s a mentality that perfectly jives with growing up poor; all you need to have fun is a skateboard and you are free. You can go anywhere and do anything. Like riding a bike, skating feels like flying.

Sexism and inclusivity issues aside, while I love the community that is such a major part of skating, in the end, skateboarding comes down to you against yourself. A beautiful, brutal battle with yourself wherein you know getting hurt is inevitable. It’s the price of admission.

It takes hard work and consistent dedication to master a new trick so when you see a good skater, it isn’t just that the tricks themselves are incredible, it’s the hundreds of falls and all the injuries leading up to the accomplishment that enhances the beauty of what you behold. In many ways, the behind-the-scenes mastery of a trick is far more impressive than the actual trick.

Reminds me of the commencement speech former tennis pro Roger Federer gave at Dartmouth a month ago. As Kottke.org noted, “after asserting that he’d graduated (and not retired) from professional tennis, Federer shared what he learned from his years on the pro circuit.”

“Effortless”… is a myth.

I mean it.

I say that as someone who has heard that word a lot. “Effortless.”

People would say my play was effortless. Most of the time, they meant it as a compliment… But it used to frustrate me when they would say, “He barely broke a sweat!”

Or “Is he even trying?”

The truth is, I had to work very hard… to make it look easy.

When someone is so good at something they make it appear to be easy, effortless, yet you know gallons of blood, sweat and tears were spilled in the battle for mastery.

Mountain biking has been like that for me just as road biking was before that. Clipping shoes into pedals, I knew I would eat shit at some point and I most definitely did in very public and humiliating ways, including at an intersection in front of dozens of people stopped at a red light. But it’s a rite of passage, part of the biking journey. You get knocked down, but get up again. And again and again. It’s the essence of being alive distilled to life’s most poignant lesson.

Nothing better reflects this courageous mentality than the June 27, 1999 X Games when a 31-year-old (ancient by skating standards) Tony Hawk, one of the most successful vertical pro skateboarders in the world, finally lands the 900 after ten failed attempts.

Hawk goes into what appears to be a trance and you can see him enter another dimension. Dude is In. The. Zone. He won’t stop. Can’t stop. Nothing in his being will allow him to stop trying.

I have watched this video dozens of times and I get chills every single time.

Hawk would’ve kept going until he landed it. He didn’t care who was there, who was watching. He just goes hard, tweaking and dialing it in after each failure. Falling and getting up over and over again. It’s such a pure, beautiful odyssey to witness. Had he not finally landed it when he did, I suspect he would’ve still been trying at midnight, a clean-up crew there waiting to flip off the lights and go home.

“The drive to always be a better person is crystalized in skateboarding. You do something and you fall down and what do you do? You get up. And you do it again. Who has that kind of determination? To go through something that causes you pain; emotional pain, physical pain,” early female skateboarder (we’re talking mid-seventies) Di Dootson said in Hawk’s documentary. “The pride that comes from meeting the challenge, passing through the challenge, is like nothing that anybody can hand you. I mean, that’s a different kind of person. Those are my favorite kind of people.”

Mine too.

Here we are 25 years later with a bookend video to Hawk’s, this time a 14-year-old girl seemingly casually nails a 900 in this incredible moment for women and full circle moment for the sport.

Female skateboarders have been a part of the scene for decades but have been overlooked and underrepresented in media and competitions. So, 40 years after skateboarding first landed on my radar, it’s exciting to see this slowly changing. Female skaters are breaking through and gaining recognition.

“I’m so stoked that it’s become an accepted thing for girls to be skating,” early female skater Leigh Parkin said in the documentary. “The girls themselves decided, ‘You know what, I’m just gonna skate. I don’t care what people think of me, I don’t care what people say, I’m gonna go skate.”

The proliferation of skate parks across California and then the country has had a profound impact on the perception of the availability of the sport to girls who no longer have to deal with sexist dudes gatekeeping the sport.

”The state of women’s skateboarding today is better than ever. I can only assume free skate parks are helping to support women in skating because they can just show up and they don’t have to go through a whole process and sign waivers and pay, the idea that it’s open to them goes a long way,” Hawk said.

I feel such sadness and anger that skating didn’t seem like it was in the realm of possibility for me but I am so fucking happy to see females excelling in the first sport I ever loved and yeah, I feel a little jealous too. Trew is young and skateboarding is welcoming her in a way it never did for me. And never will. I’m too old now.

Still. It won’t stop me from dragging my old ass outside whenever I see a freshly paved local road, broken bones be damned. The sound of wheels, smooth as silk, gliding across asphalt, still does it for me.

And this time I’m the one making the sound.

That last line tho 😭❤️🔥 THAT’S MY GIRLLLL.

Oh my gosh, I love that you were a skater girl. I didn't realize it was so sexist back in the day. That's so cool that you did that for your kids. I wish I had learned to skateboard. I was too afraid. Now I'd probably break something lol I love the video of you, too. So cool.